The Ruling Ladies of the Low Countries: Introducing the Series!

From the Duchy of Burgundy to the Archducal Netherlands, women ruled as sovereigns, governors, and regents for one hundred and fifty years

Many readers will have heard of women ruling in Europe during the sixteenth century. Catherine de Medici dominated French politics and Elizabeth I directed a golden age in England. Elizabeth’s elder sister Mary was sovereign before her, and her relative Mary Stuart, Queen of Scots, was one of her great rivals.

But did you know that during this same era women were ruling in the Netherlands?

The Netherlands (or Low Countries, I’ll use the two interchangeably) was the sovereign Duchy of Burgundy from the late 1300s when, upon the death of the region’s count, the Valois King of France named his son Philip the Bold to be the first Duke of Burgundy.

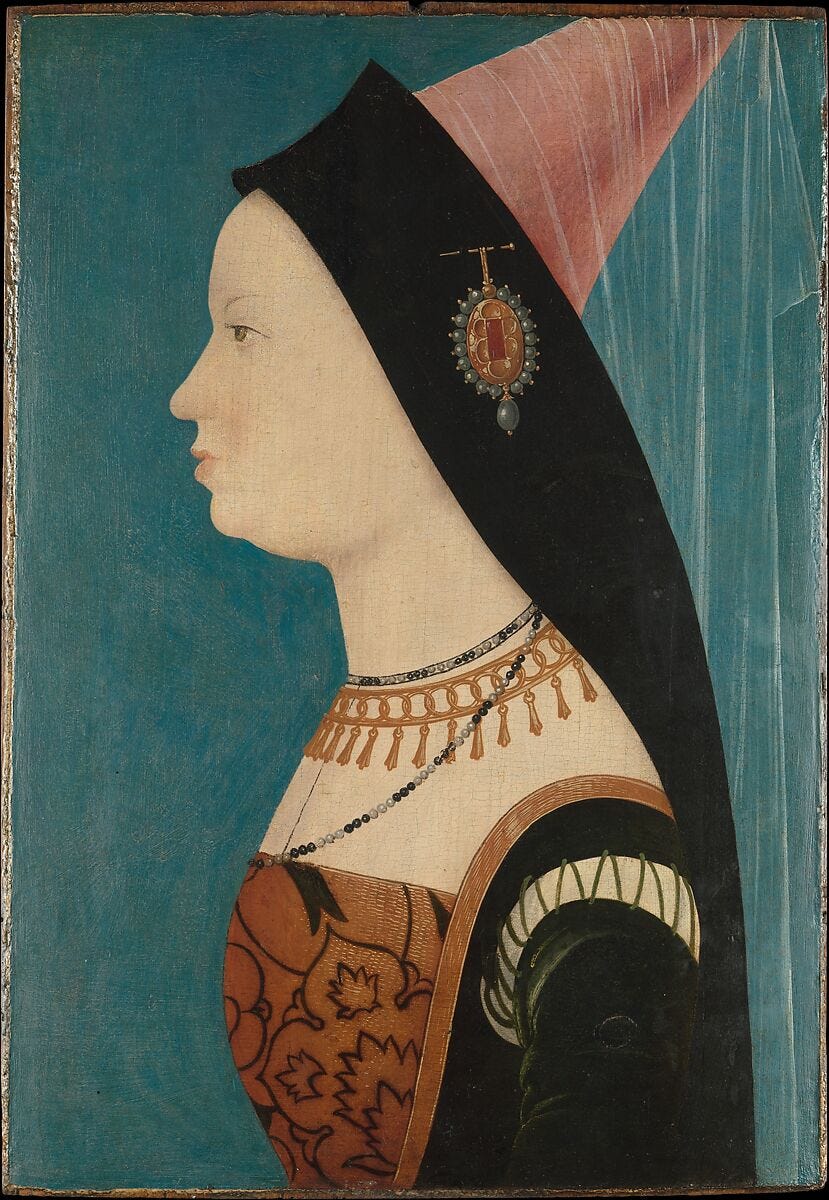

The Duchy of Burgundy came to represent the height of medieval culture in northern Europe, attracting the best artists, musicians, and courtiers from across the continent. It remained an independent powerhouse for a century, when the death of Charles the Bold at the Battle of Nancy (1477) brought his daughter and heir, Mary of Burgundy, into power. She was the final sovereign Duchess of Burgundy. As she married Maximilian I Habsburg (for reasons we’ll get into later), control of the Duchy transferred to the Habsburg Empire upon her death.

Mary died tragically in 1482, and from then on the Habsburg men in charge were absent more often than present in Burgundy. As a far-flung piece of a massive Empire, the Netherlands required a stable government to oversee its daily administration, to defend Habsburg authority in the absence of its kings.

From Maximilian I to his great-great-great grandson, King Philip IV of Spain, Habsburg kings consistently nominated the women of their family to rule in their stead in the Low Countries.

In the long sixteenth century (this is just how historians describe a century when they’re including extra years at either end), massive changes occurred across Europe, and in the Netherlands specifically. The religious wars that sprung from the Reformation intensified a fraught situation, as the hardcore Catholicism of the Spanish Habsburgs clashed with the Calvinist tendencies and practical religious outlook common to the Netherlands - especially the northern provinces.

This religious disconnect between the king and his people made the mediation of the governor all the more important, as they defended (with varying levels of success) the proudly held local traditions from the increasing oppression of Spain. In all cases, they faced an impossible position. They could only govern if they won the respect of their people, and to do that they had to champion practical compromises for self-governance and religious freedom. But to endorse those policies often meant angering the Most Catholic King, who placed them in power and could remove them at his pleasure. The governors’ success depended upon their personal relationship with the king - as well as the particular chaos that defined their era.

Of all the women who ruled in the sixteenth century, the Governors of the Netherlands, I find, rarely get enough credit. The history of this region might be overlooked, in part, because it was so complicated. The governors spent much of their time balancing disparate interests - and defending their decisions to one party or the other. Add religious conflict, civil violence, and international interference to the mix, and it’s easy to understand how the history of the Low Countries (which, I should mention, also split in half in the 1580s) is tricky to sum up neatly.

But it sounds like a fun challenge!

So I’m thrilled to introduce my first ever series for Feminist Histories: The Ruling Ladies of the Low Countries!

In this five-part series, I will share the histories of the women who ruled in the early-modern Netherlands, nearly uninterrupted, for a hundred and fifty years. They were the aunts, sisters, and daughters of the Habsburg Kings. But more importantly (at least to the people of the Netherlands) they were direct descendants of Mary of Burgundy.

The first post will introduce Burgundy as a sovereign Duchy, focusing on the late fifteenth century when Mary of Burgundy came to power.

The second will revolve around Margaret of Austria, Mary’s daughter, who governed in the absence of her father, Maximilian I Habsburg, and during the youth of her nephew, Charles V, from 1507-1530.

The third installment covers the rule of Mary of Hungary, Charles V’s sister, who governed from Margaret of Austria’s death until 1555, after a brief, ill-fated marriage to the King of Hungary.

Part four introduces Margaret of Parma, a natural-born daughter of Charles V and half-sister of Spanish King Philip II. Margaret ruled in the Netherlands at the outbreak of the Dutch Revolt, as Philip II increasingly cracked down on religious dissidence. Her tenure began in 1559 and ended in 1582 - with an interlude from 1567-1578 (which, you guessed it, I’ll explain when we get there).

I’ll just come right out and say it - Margaret of Parma really drew the short stick in terms of what she had to deal with.

The fifth and final segment represents the culmination of female rule in the Netherlands under the Archduchess Isabella Clara Eugenia. A daughter of Philip II and Elizabeth of Valois (daughter of Catherine de Medici), Isabella’s dowry included sovereignty in the Netherlands for herself and her husband, Archduke Albert VII of Austria. The Archdukes ruled together from 1599 until Albert’s death in 1621. Isabella stayed on in a demoted role, as governor, from Albert’s death to her own in 1633.

In the Netherlandish imagination, the rule of the Archdukes represented the long-awaited return of the glory of old Burgundy- delivered by Mary of Burgundy’s great-great-granddaughter.

I hope you enjoy this series as much as I will enjoy sharing it! Part I, the story of Mary of Burgundy, will be arriving in your inboxes soon!

If you’d like to support my work, you can also:

I’m always up for this sort of thing, especially after writing a science fantasy that draws on the legends of Melusine of Lusignan as well as the descendants of Catherine de Medici….

I'm really looking forward to this series. As a Tudorphile I have a little knowledge of Margaret of Austria (mainly courtesy of Natalie Grueniger and Owen Emmersons fascinating lecture series on Anne Boleyns early years) but i have little knowledge of pretty much anyone else mentioned. I can't wait to be enlightened!