Margaret de la Marck, Princess-Countess of Arenberg

The most powerful princess you've never heard of.

Introduction

Margaret de la Marck was one of the most well-traveled women of sixteenth century Europe. By the time of her death in 1599 she had gained fame and influence across all the major courts, and her children and grandchildren would continue to build upon the dynasty that she founded.

I’m telling Margaret’s story today because she was one of the most pleasant surprises I’ve found in my research. I was not looking for her, and yet she is probably the best example of all the different things I wanted to say about early modern noblewomen. She could be an amalgam of all the most impressive parts of the ladies I discuss, and yet she, herself, existed. How exciting!

After years of investigating her story, it seems that her foundational strategy for politics was the pursuit of transregional power. It was good to have friends in high places, and the more friends in the more high places, the better.

Margaret spent much of her life crossing borders. For a long time, history has been defined by borders, but this is not an accurate representation of early modern life. Simply put, early modern borders were often aspirational at best, with cultures, languages, and even recognized authorities overlapping with each other. Borderlands regions functioned much more like Venn diagrams than concrete divides.

Members of the nobility felt this flexibility on a different scale. Noble families’ claims to regional authority could easily be more ancient than the power of monarchies. Borders between kingdoms moved across them, rather than the other way around. The most successful families understood that their power was best protected through balance, where they ingratiated themselves to their monarchs while also fighting to preserve traditions and privileges they’d enjoyed before their arrival.1

This brings us back to Margaret de la Marck, whose political career was a veritable who’s who of the most powerful families in France, Spain, the Holy Roman Empire, the Italian states, and the many sovereignties in between.

Margaret de la Marck’s story also serves as prologue to a larger story I’ll be sharing soon about women in transregional diplomacy. My next post for Feminist Histories will share the political undertakings of Marguerite de Valois, Princess of France and Queen of Navarre, as she traveled across the Netherlands in the 1570s. Margaret de la Marck was one of the most powerful women who entered into negotiations with the Queen, but she wasn’t close to being the only woman involved. Helping to set up the story that will follow, Margaret de la Marck provides an excellent example of just how intertwined politics and society were in this period, even across borders.2

Heiress to the Arenberg

Margaret de la Marck was born in February 1527, a member of the powerful Arenberg family. Arenberg power can be traced to the middle ages, in the Eiffel region of the Holy Roman Empire.3

The younger child of Robert II of la Marck and Walburge of Egmont, Margaret lived with her aunt and uncle in nearby Isenburg until she was eleven years old. But life came at her fast, and when Margaret’s elder brother died, she became sole heiress at only ten years old. The hopes of the Arenberg dynasty’s future lay on her young shoulders.

Soon after her brother’s death Margaret went to reside with her grandparents, Robert I of la Marck and Mathilde of Montfort, in the Spanish Netherlands. Mathilde of Montfort was heiress to vast Netherlandish land holdings which joined the Arenberg patrimony. Adding political clout to landed power, Margaret’s grandfather was appointed by Holy Roman Emperor Charles V - sovereign in the Netherlands - to assist his Regent (and Aunt) Margaret of Austria, in her administration of the government. This meant that Margaret de la Marck spent her adolescent years becoming familiar with the ins and outs of the Netherlands court and administration.

Context [and a teaser!]:

Holy Roman Emperor Charles V administered his realms nomadically, traveling between the German States, Spain, and the Netherlands throughout his reign - not to mention his years fighting in the Italian Wars. Because of this, he relied upon appointed governors to rule in the Netherlands on his behalf. For nearly two hundred years, from Charles V to his great-grandson, Philip IV, the Habsburg Netherlands were governed (barring a few interludes) by women: first Charles V’s aunt, then his sister, then his daughter, then his granddaughter.

I won’t say too much about this now, because I am working on a series which will speak about each of these fabulous women in much greater detail. Watch this space!

Marriage & Politics

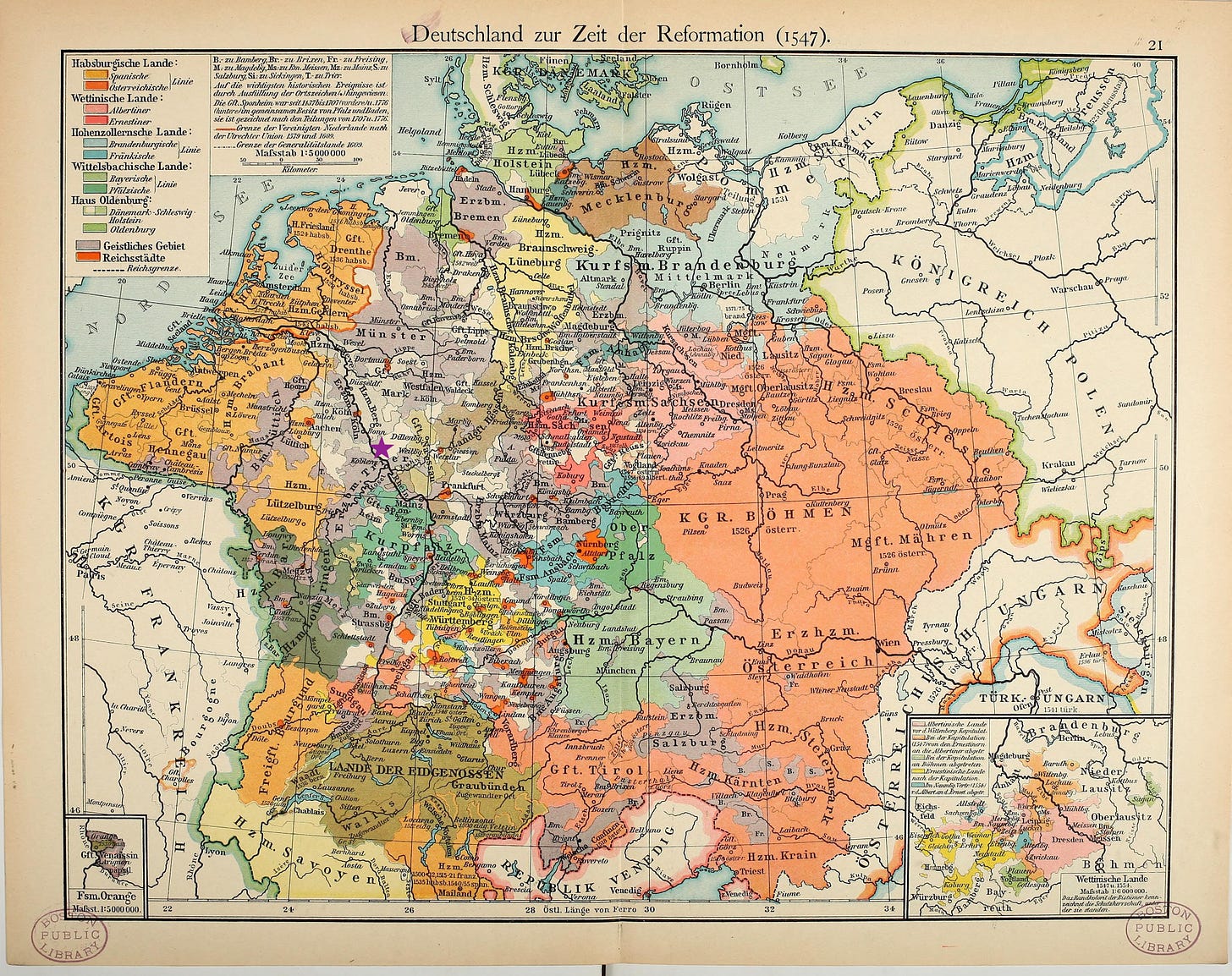

Margaret de la Marck’s step onto the political scene required that she, of course, find a valuable marriage partner.4 In 1547, twenty-year-old Margaret married Jean de Ligne, the Baron of Barbançon (a region in modern-day southern Belgium) and a Knight of the Golden Fleece.5 The de Ligne were an ancient noble families dating at least to the 1200s. Jean de Ligne held the position of Stadtholder, a sort of magistrate appointed by the emperor, of Groningen, Frisia, and Drenthe.

In a refreshing break from the trend, Jean and Margaret were only two years apart in age.

While we’re on the topic - It was specifically noble and royal families who married so young, and with such great age differences, in order to secure alliances. Among the 99%, marriages usually occurred around the same ages for men and women as they do today, with women in their mid-ish-20s and men in their early 30s, more or less.

With the de la Marck holding lands in the Netherlands and the Empire, as well as sovereignty in the principality of nearby Sedan, marriage to Margaret was a boon to Jean de Ligne and his family more so than the other way around.6 Proof of this was the special privilege that Charles V granted the couple - their marriage contract stipulated that Jean and the couple’s descendants would adopt the name and coat of arms of the Arenberg. This allowed the more prestigious Arenberg name to survive its transfer into the female line. And the family name did continue: the couple were by all accounts happy and productive, producing six children, four of whom survived childhood.7

Right on the heels of their 1547 marriage, Margaret and Jean took position as powerful players in the court of the Netherlands. Within two years they notably attended the first of their many appearances at significant moments in Habsburg politics: the entry of future king Philip II.

In 1549 Charles V was planning to introduce his son and heir, Philip, to the lands he would eventually inherit. Charles and his sister Mary of Hungary, Regent in the Netherlands, traveled with Philip across the Empire, visiting the major cities and getting a sense of the local dynamics he would have to manage. The trio’s entries were celebrated with feasts and tournaments to entertain the court and impress the country’s leading nobility.

The Arenberg couple were also quick to establish themselves as a transregional force. After attending the Habsburg entry to Brussels, the couple traveled to Margaret’s lands in Arenberg. Margaret kept close tabs on the running of her dispersed land holdings, so the visit allowed her to check in on their management while also introducing her new husband to her wider patrimony. The newlyweds spent nearly a year there before returning to the Netherlands.

In 1550, Charles V announced that he was going to war against French King Henry II, escalating an ongoing dispute over lands in Italy. Receiving “honorable charges” from the emperor, the wars marked the next stage of Jean de Ligne’s political rise. His service to the Habsburgs reinforced their fealty to Habsburg authority.

At the same time, Margaret began to grow their family. In 1550 she gave birth to her son and eventual heir, Charles. It seemed that for much of the 1550s Margaret returned her attention to the court of the Netherlands. During this time, she developed friendships with the most powerful women at the Netherlands Court: Regent Mary of Hungary, Eleanor of Austria, and Christina of Denmark.

Eleanor of Austria was the widow (since 1547) of king Francis I, as well as the sister of Charles V and Mary of Hungary. Christina of Denmark was the Duchess of Lorraine, a sovereignty resting between France, the Netherlands, and the Empire. Christina served as Regent of Lorraine, governing on behalf of her young son Charles since the death of his father.

That is, until King Henry II of France invaded. In 1552 Henry II took the young duke prisoner, forcing him to separate from his family to reside at the French court. With the young Charles in his custody, Henry II placed his own authorities in Lorraine and forced Christina of Denmark and her daughters to seek refuge elsewhere.

Dowager Queen Eleanor of Austria left France to live out the rest of her days with her siblings (it seems the three Habsburgs were quite close, and it’s a relationship I look forward to learning more about in my series on the Regents!). Stopping in Lorraine on the way to her sister Mary’s court, Queen Eleanor invited Christina of Denmark to join her. Together the ladies arrived in Brussels in April of 1554.

I wish I had more information on how Margaret grew close to Eleanor and Christina. She certainly would have known Mary of Hungary well by that time, and perhaps Mary introduced Margaret de la Marck to her sister from France. My earliest evidence of their friendship comes from the fact that when Margaret gave birth to her son Emmanuel in 1556, she named Mary of Hungary and Christina of Denmark as his godmothers. The godfathers were Emanuel Philibert, the Duke of Savoy, and Lamoral d’Egmont, the Count of Hoorn.8

Godparentage was an incredibly powerful symbol in early modern history, and a strong indicator of alliance among the political classes. So not only were these powerful women bonded to Margaret through friendship, but their favor would be expected to extend to future generations of her family.

Changes in the Empire

Many seismic shifts occurred in the Habsburg orbit across the late 1550s. Charles V retired officially from rulership in 1555, leaving the Holy Roman Emperor to his brother Ferdinand I, and Spain and the Netherlands to his son Philip II.

In 1556 the new king Philip II gained yet another title as he departed for England to marry Mary I, eldest daughter of Henry VIII. (Though it’s also fun to note that the title wasn’t all Philip hoped it would be: Mary refused to name him King, leaving him as her King Consort, a position with greatly limited powers).

Charles V and his sisters departed the Netherlands to retire from public life for good. Marking one of the interludes in female governance, the Regent for the next four years was none other than the Duke of Savoy - one of the esteemed godfathers of Margaret’s youngest son. Margaret de la Marck was in Brussels to say her goodbyes to the Habsburg siblings before their voyage to Spain.9

Only a year later Margaret de la Marck attended yet another moment of political significance. This time, her presence was requested at the signing of the treaty to end the Italian Wars. This peace, known as the Treaty of Cateau-Cambrésis, had been achieved by the intervention of Mary of Hungary, Eleanor of Austria, and Claude of Valois. The sisters of Charles V came together with the Princess Claude of France - by now Duchess of Lorraine. Claude was the eldest daughter of Henry II and Catherine de Medici. As she married Charles III, Christina of Denmark’s son, Charles’ captive upbringing at French court had made him not an enemy of France, but an ally.

It should be no surprise that with these women in charge of negotiations to end the wars between their father and brother, Margaret de la Marck was welcome to share in their counsel and the celebration of their diplomatic victory.

But King Philip II was preparing to make his return to the continent. Charles V died while the treaty negotiations were ongoing, and Philip’s wife Mary I of England died around the same time, leaving Philip II a widower. (In another personal blow, Philip’s proposal to marry Mary Tudor’s half-sister and successor, Elizabeth I, was roundly rejected.)

Philip II traveled through the Netherlands on his way to Spain in 1559, and Jean de Ligne and Margaret de la Marck joined the envoy to escort him south. When Philip II chose his half-sister, Margaret of Parma, to take up the Regency in the Netherlands, The Arenbergs returned to the Netherlands in the new Regent’s company.

These types of escorts included both men and women of the nobility, and the journey was a good chance to establish relationships at the start of a new regime. The Arenbergs seemed to succeed at this, as the new Regent interceded with Philip II on multiple occasions to grant them further lands and titles.

Personally, Jean de Ligne didn’t make too much of an impression on Philip II: it would be years before Jean gained a leadership position in his service, and Philip noticed that the Arenberg continued to divide their attention and loyalties.

But with the firm favor of Margaret of Parma, the couple continued to travel and pursue their transregional careers. In 1560 Margaret traveled with Claude of Valois to the Empire to attend the coronation of Emperor Maximilien II in Frankfort, and she visited Lorraine frequently in the years that followed. In 1566 Claude asked Margaret to take part in her son’s baptism, where she would have also reunited with her friend Christina of Denmark. Their friendship with Christina of Denmark now represented an intergenerational alliance between the Arenberg and Lorraine.

Margaret the Widow

At the Dutch Revolt progressed, the staunchly Catholic Arenberg hedged their bets, seeming to put politics ahead of religious unity. But Jean de Ligne’s position as Stadtholder in Groningen and Frisia - two provinces in the heart of the Calvinist stronghold of the Northern Netherlands - meant Philip II would need to lean on the Count of Arenberg eventually. When the Arenberg’s good friend Margaret of Parma retired - a response to Philip II bringing the antagonistic lieutenant general Alva to the Netherlands - Jean de Ligne was sent to repel the rebel offensive in Groningen.

The ensuing battle was long considered the official start to the Dutch Revolt, though of course historians now recognize that events were more complicated than that. The Battle of Heiligerlee, however, remains one of the most famous and consequential military battles in early modern history.

The armies of the Prince of Orange, William the Silent, were led by his brother Adolf of Nassau against the royalists under Jean de Ligne. Both Jean and Adolf died in the battle, and the royalists troops fell apart following the loss of their leader. The battle was the first major victory for the rebels in the Dutch Revolt. To add insult to injury, the Prince of Orange avenged his brother’s death by ordering his men to ransack the Arenberg lands - destruction which would not be fully rectified in Margaret’s lifetime.

Though her husband’s prestige in Philip II’s military was relatively short-lived, Margaret used Jean’s loss to affirm the Arenberg legacy of Habsburg loyalty. Margaret and future Arenbergs consistently referenced Jean de Ligne’s sacrifice at Heiligerlee as an example of their defense of the Habsburg regime and the Catholic Faith. Margaret did this even while she continued to maintain arms-length from the conflict, whenever possible.

Margaret’s highest priority was to protect her eldest son and heir, Charles of Arenberg, and to set him on a trajectory to ensure his successful political career - not just within the Netherlands, but in the broader Habsburg composite monarchy. Margaret had cultivated relationships with powerful allies across Europe, which she expanded through extensive travel and correspondence. These contacts helped her secure prestigious commissions for the young Count of Arenberg. It was no coincidence that the assignments kept Charles far from the warfronts, keeping him occupied in ways that precluded military service.

Charles’ first major appointment was to join an envoy to the French court of Charles IX and his mother Catherine de Medici - Philip II (by then Catherine de Medici’s son-in-law) sent an embassy with his congratulations for the recent royal victory over the French Huguenots.10

Charles continued in his parents’ footsteps as a well-traveled and active nobleman. After Charles’ return from France in 1570, Margaret and Charles were soon involved in another royal envoy. The eldest daughter of the emperor, Anna of Austria, traveled to Spain to become the fourth wife of Philip II (his third wife, Elizabeth of Valois, had died two years prior). Margaret and Charles met the bride in Berghe, after which Charles joined her escort to Spain.

Bridal embassies representing the unification of the royal houses, and they included courtiers from both the bride’s country of origin and her new marital home. The courtiers chosen to join them were tasked with smoothing the entry to the bride’s new court - some to help her become acquainted with her new people and culture and others to provide comfort and familiarity from her homeland. A bridal escort was also a massive opportunity for the courtiers involved - for Charles, Anna of Austria’s envoy provided his first chance to establish his reputation at the Spanish court. Margaret de la Marck spared no expense to assure that Charles and his entourage exhibited the wealth and value of the Arenberg name.

With Charles safely heading for Spain, Margaret turned her attentions to the service of another Imperial wedding, joining the bridal party of another of the emperor’s daughters. Traveling to Spire, Margaret met Elizabeth of Austria, the betrothed of King Charles IX of France. Traveling as part of the Archduchess’ household, Margaret was warmly received by the French court: it seems her son’s recent visit made a good impression. Margaret was gifted a fine necklace and other valuables by Queen Mother Catherine de Medici in recognition of her service.

The Italian Tour

Margaret undertook her longest journey on record from late 1574, beginning an extended tour through Italy’s finest courts on her way to meet with the new Pope, Gregory XIII, in Rome. But in her many stops along the way, Margaret prioritized visits with the powerful women of the Habsburg family who populated the Italian courts.

Margaret visited Mantua first, spending time with the Duke of Mantua and his wife, Eleanor of Austria. This Eleanor of Austria was another daughter of the emperor (and for clarity’s sake I’ll refer to her as the Duchess of Mantua from here on). The Duchess joined Margaret as she continued her travels to the court of Ferrara (the Duchess of Ferrara, who died two years earlier, was also a daughter of Ferdinand I, and thus the Duchess of Mantua’s sister.)

In Ferrara, the women kept company with the Duchess of Urbino, Vittoria Farnese. Vittoria was the sister of the Duke of Parma, and therefore sister-in-law to Margaret of Parma, the Arenberg couple’s close friend. Margaret then traveled on to Parma to visit Margaret of Parma herself, as at that time she was between her two tenures in the Governance of the Netherlands.

Reaching Rome, Margaret remained there until 1575, when she began her journey north. She visited Florence and Boulogne, returned for another visit to Parma, then continued on to Plaisance, Pavia, and Milan.

Though records omit the details, these types of visits between high nobility were always political. They served to create or enhance friendships, invite people into one’s political network, and provide private opportunities to discuss important events, plans, and successions - the types of things which smartly would be left out of written records. Traveling between the courts of several sisters of the Holy Roman Emperor in quick succession, Margaret was even more fully intertwining herself with Imperial interests and service.

Margaret returned to the Netherlands from Italy, though the Discourse which forms the central source for this story does not mention this. I belatedly discovered her return home from her own letters, which she exchanged regularly with the Duke of Alva. In September 1575 Margaret wrote the Duke from Italy, but by November she was posting her letters from her Chateau of Mirwart.11

SUPER Fun Fact! The Chateau of Mirwart, a favorite of Margaret’s, has been renovated and is now a hotel. Spending a weekend in Margaret’s home has skyrocketed to the top of my bucket list.

While in the Netherlands, Margaret wrote to Alva that she had been invited by Elizabeth of Austria to escort her from France, where she was recently widowed, to reunite with her father the emperor. Margaret had attended Elizabeth in her bridal escort, and now she returned to her service in widowhood. From this journey Margaret traveled south to Savoy, where it seems the Duchess of Mantua - the newly widowed Elizabeth’s aunt - joined her traveling party.

Together Margaret and the Duchess traveled through Lorraine and on to Munich, where they were joined by the Duke and Duchess of Bavaria (you guessed it, Duchess Anne of Austria was yet another daughter of Ferdinand I and sister of Maximilien II). The impressive party continued on to the court in Vienna, where they were received by the emperor - Maximilien II, the brother of the many Austrian Archduchesses Margaret met in her travels - and Empress Mary of Austria (a daughter of Charles V).

It was during this visit to the Imperial Court that Margaret and Charles received the highest honors they would obtain - the titles of Prince and Princess of the Holy Roman Empire. With this promotion Arenberg was raised to a Princely County, which gave them a seat and vote in the Imperial Diet (the Holy Roman Empire’s main deliberative body). The honors were specifically in response to their service to the emperor, particularly in the bridal parties of Habsburg women.

Conclusions

Margaret de la Marck returned to Brussels in time to witness a turning point in the ongoing Dutch Revolt: the Pacification of Ghent (November 1576). This was a victory for the Netherlandish nobility, as noble Calvinist and Catholic leaders came together to demand that Philip II expel all Spanish troops from the Netherlands. The fact that Margaret de la Marck then traveled to Dordrecht, to meet with the Dutch Rebel leader William the Silent on his own turf, says much about her continued balancing of interests, between fealty to Spain, the Empire, and her own interests.

Margaret de la Marck was above all a woman who kept her options open. She was meticulous in creating relationships in the courts across Europe, which allowed her to advocate for herself and family with impressive flexibility. Her transregional reputation allowed her to become one of the most well-traveled and well-connected noblewomen of the early modern era.

How Margaret continued to use this power, particularly through the growing turbulences of the religious wars, will have to wait until my next post.

If you’d like to financially support my writing, you can also:

For more insights into transregional history and nobility studies and frameworks in historical research, check out “How to do Transregional History: A Concept, Method and Tool for Early Modern Border Research,” Journal of Early Modern History 21 (2017), 1-22.

The central discourse that informs this research is housed in the Arenberg archives in Enghien, Belgium. It was written 25 years after Margaret’s death, when the Arenberg dynasty, headed by Margaret’s daughter-in-law, Anne de Croÿ created the a family archive which survives to this day. Luckily, and unlike many similar initiatives, Anne preserved the Arenberg women’s legacies as much as possible. Brief discours de la vie et conduicte des affaires de Marguerite de la Marck Comtesse de la Marck et d’Arembergh depuis sa naissance (1624) AA Bio 35 / 8 / 3C, fol. 1-16.

Veronika Hyden-Hanscho, “State services, fortuitous marriages, and conspiracies: Trans-territorial family strategies between Madrid, Brussels, and Vienna in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries,” Journal of Modern European History 19, no. 1 (2021), 47-48.

We know she remained with her grandmother for three years after her grandfather’s death, but unfortunately of the intervening 3-4 years, I have no idea of where she was or what she was up to. ALTHOUGH, a big disclaimer here: there is a lot of further information on Margaret and her family in German and Dutch language records, in addition to those in French. I’m not the best in those languages so I avoid drawing too many concrete conclusions on what, exactly, is the extent of “our knowledge.”

The most prestigious chivalric orders of the era, the Order of the knights of the Golden Fleece was started in 1430 by Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy. It still exists today!

Violet Soen, “From the Battle of Heiligerlee to the Act of Cession: Arenberg During the Dutch Revolt,” in Arenberg, Derez, Vanhauwaert and Vergrugge, eds. (Brepols, 2018), 89.

Généalogie de la Maison Princière et Ducale d’Arenberg (1547-1940), 20-21.

As Margaret de la Marck’s mother was a d’Egmont, as was the Count of Hoorn, Lamoral d’Egmont.

Jean might have been there, but I’ve only found confirmation of her attendance.

Soen, 91. Given the date and grandiose nature of this embassy, it was highly likely in response to the Battle of Jarnac, when the royal armies defeated the Huguenots and killed their military leader, the Prince of Condé.

Letters between Margaret de la Marck and the Duke of Alva, 1570-1578. Archives Générales du Royaume (Brussels, Belgium), Papiers de l’État et l’Audience, 1732.2/C.

Further References

Jonathan Israel, Conflicts of Empires: Spain, the Low Countries and the Struggle for World Supremacy, 1585-1713 (The Hambledon Press, 1997).

Liesbeth Geevers, The Spanish Habsburgs and Dynastic Rule, 1500-1700 (Routledge, 2023).

Mirella Marini, “From Arenberg to Aarschot and Back Again: Female Inheritance and the Disputed ‘Merger’ of Two Aristocratic Identities,” in Dynastic Identity in Early Modern Europe (Routledge, 2015).

Peter Neu, Margaretha von der Marck (1527-1599): Landesmutter, Geschäftsfrau und Händerin, Katholikin. Eine Gerfüstete Gräfin in Einer Zeit Grosser Umbrüche (Enghien: Fondation d’Arenberg, 2013).

Peter Van Der Limm, The Dutch Revolt 1559-1648 (Routledge, 1989).

Transregional Territories: Crossing Borders in the Early Modern Low Countries and Beyond, De Ridder, Soen, Thomas, and Verreyken, eds. (Brepols: Turnhout, 2020).