Queen Margot, the Diplomat

Marguerite de Valois' secret campaign in the Netherlands and the powerful women she met along the way.

Introduction

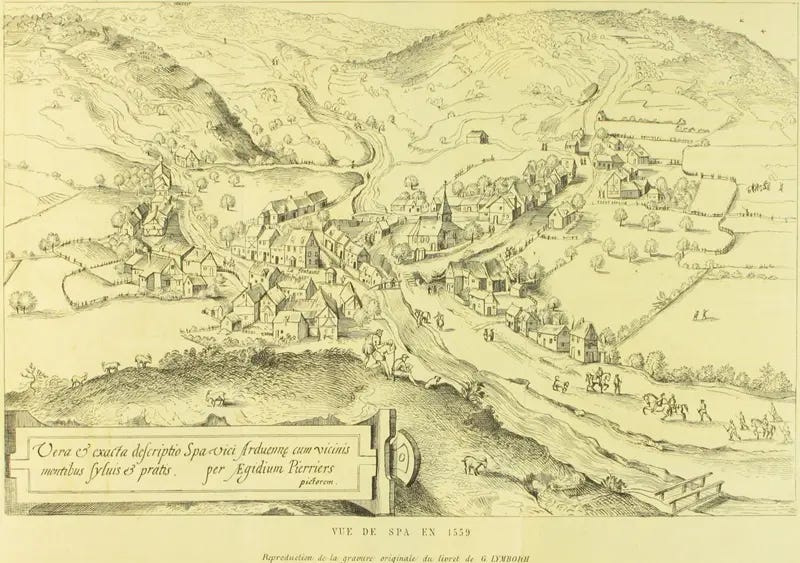

During the summer of 1577 Marguerite de Valois took a journey across the Southern Netherlands to enjoy the healing waters in the famed town of Spa. In this era many wealthy women traveled impressive distances to enjoy the medicinal properties of natural spas, which boasted everything from curing illness to encouraging fertility, providing beauty remedies and combating mental and emotional ailments. But while Margot certainly would enjoy “taking the waters” (she dealt with a recurrent inflammation on her arm), this was not the true motivation for her journey.

I’ve been excited to bring this story to Feminist Histories since I first had the idea to start it. It is a story of intrigue, politics under cover, women in charge, and it centers on one of the most famous women of the age - conducting diplomacy in a capacity that no one gives her credit for.

This story caught me by surprise in the archives, in the best possible way! I was fairly familiar with Marguerite de Valois through my more in-depth studies of her mother, Catherine de Medici, and of early modern noblewomen more broadly. But I was in a small Belgian archive when her name popped up in the most unlikely of places.

Remember Margaret de la Marck, Princess-Countess of Arenberg, from last month’s post? Well, in a letter to a friend in 1577, she mentioned that she’d met with The Queen of Navarre in Liège. This was not a flex or even a point of interest for Margaret, but a passing complaint - the visit got in the way of pursuing other priorities. I was thoroughly impressed by Margaret de la Marck’s nonchalance and entertained by her lack of interest in this international celebrity.

As it turns out, the rabbit hole this reference led me down and the story I found there ended up having little of Margaret de la Marck in it. But she was there, as was her daughter, and several other powerful women of the Southern Netherlands. (And of course, a bunch of men, too.)

Marguerite de Valois: La Reine Margot

Marguerite de Valois is most often remembered as she was described by sensationalist (and misogynist) historians who wrote about her long after the fact. I’m talking about you, Alexandre Dumas. The success of Dumas’ La Reine Margot continues today, with a number of adaptations for theater, TV, and film. These adaptations are heavy handed with sexual allegations and scandals - so it makes sense that many casual observers assume Marguerite de Valois was frivolous, shallow, and promiscuous. As an extension of this, and due to the lack of interest in other elements of her life, Margot has long held a reputation as being essentially a political lightweight.

A note on names

I recognize that the nickname “Margot” was not used during Marguerite de Valois’ lifetime and really came into vogue through later literature. But there are three Margarets in this story - Valois, de la Marck, and Ligne - so for clarity’s sake, I’ll make use of Margot, when I’m not using her full name or title.

I’m not going to comment on Margot’s potential sex life. Frankly, I don’t care about who she might have been entangled with or loved. Her body, her choice, etc. The early modern 1% married for political stability and power - and the men among them were fully expected to have extramarital sexual relationships. In fact, if they didn’t, their reputation as virile and masculine “enough” could be damaged. So, I present that double standard for your consideration, and I’m just going to slide right past Margot’s personal life to get to the interesting stuff. Margot became a powerful political player in her own right, and today I’m writing about a mission that helped to establish her political agency.

Traveling across the Netherlands in 1577, Margot sought alliances with Dutch nobility to support her brother Anjou’s campaign to oust Philip II and replace him as sovereign. She played her part so smoothly that the Dutch States General and French monarchies both credited her influence, and Anjou’s campaign went much further than it otherwise would have (though we will see, he was still ultimately unsuccessful, having played his own part poorly.) But Margot laid the groundwork for his operation, and the credit she gained in the process earned her a central diplomatic role in the years that followed, when she served as a moderator and negotiator between her mother and husband in the ongoing Wars of Religion.

Europe in the 1570s

The 1570s was a period of intense negotiation between France and the Netherlands. The Dutch had been rebelling against their Spanish overlords for a decade, seeking the freedom to practice Calvinism and the protection of traditional noble privileges, which Spanish King Philip II continued to strip away. Dutch Calvinists and Catholics came together to demand the signing of the Perpetual Edict in early 1577, which required Philip II to remove all Spanish troops from the Netherlands. The treaty roiled the hot-headed governor of the moment, Don Juan of Austria, who fumed over the limits placed on his authority.

At the same time, France was fifteen years into its own civil wars - which also concerned, among other things, religion, governance, and noble rights. The third civil war had ended in 1570, and the French crown sought to affirm the peace by marrying Princess Marguerite de Valois to the Protestant King Henry of Navarre. The celebration of their wedding was the site of a spontaneous uprising of Catholic violence, with the mass murder of Protestants starting in Paris and spiraling throughout the French countryside in the weeks that followed. (These were the St. Bartholomew’s Day massacres, and I will be expanding on them - and particularly, Catherine de Medici’s role in them - in an upcoming post. Spoiler alert: she didn’t do it.)

The Holy Roman Empire and all the other sovereignties making up early modern Europe were facing their own debates over religion and government. News of the massacres caused an international furor, with publications across Europe speculating about what the bloodshed meant for the French Huguenots - and Protestant communities more broadly - moving forward.

The conflicts in each of these regions were intertwined, as noble, religious, and military leaders crossed borders to support their allies abroad. For some, this meddling was religiously motivated. Others sought personal gain. The latter was the case for Hercules de Valois, favorite brother of Marguerite de Valois. Anjou had been angling to improve his station for years, and in the mid-1570s, he was approached with an opportunity - to become a King, no less - if he were to intervene to support the Dutch against the Spanish.

Paris, 1576

Neither Margot nor Hercules enjoyed a particularly stable relationship with their broader family. The youngest surviving members of the Valois, their mother Catherine de Medici was more concerned with the preservation of the Valois crown than the individual Valois children’s happiness.

Since the massacres, Margot, her husband Henry of Navarre, and Hercules d’Alençon had all been discontent. Navarre was forced to convert to Catholicism, as were scores of people across France. French King Charles IX reneged on a promise to make Alençon Lieutenant-General of the realm. When Charles IX died and Henry III came to the French throne in 1575, the new King increasingly favored the hardline Catholics. Over time, a contingent of malcontent nobles, unsatisfied with their own positions in the government, coalesced around Alençon. With how things were progressing, Navarre, Alençon, and Margot all sought opportunities to flee the French court.1

In September 1575, Alençon finally managed to escape with his sister’s help: Margot lowered a rope out of the window of her chamber in Paris, by which Alençon descended, and she burned the evidence in her fireplace. In early 1576, Navarre also fled the court.2

Hercules d’Alençon took up a mediating position for the French Huguenots with the French crown, leading to the peace to end the fifth civil war in the Edict of Beaulieu. It was a personal triumph for Hercules, who gained the prestigious title Duke of Anjou in recognition of his role.

Anjou’s Ambitions

Anjou sought to build upon his recent success, and the Dutch States General under William of Orange made a well-timed request. The Dutch offered to name Anjou King in the Netherlands if he helped them oust the Spanish.

Though the Dutch hoped Anjou could eventually win them the support of the French crown, Henry III and Catherine de Medici would never consider a proposal that would threaten their hard-won alliance to Spain. Anjou couldn’t yet inform the monarchy of his ambitions, but he made a safe bet by involving his sister Margot.

Margot was still stuck at French court. Her requests to depart Paris for Navarre had been denied, but this would eventually create something of a scandal - after all, was she not a sovereign Queen as well as a French Princess? Her husband was at war against her brother, and as Queen of Navarre it was improper that she reside in the court of its enemy. Still, a good theoretical argument did not secure a favorable response from the king: she needed a good excuse, something apolitical, to depart Paris without the semblance of a political capitulation by Henry III.

In the end, it was Catherine de Medici’s dame d’honneur who provided her opportunity. During a social gathering at the court, Margot was speaking of her extended detention when the elderly Philippe de Montespedon, Princess of La Roche-sur-Yon, mentioned her upcoming journey to take the healing waters at Spa.3

A man named Mondoucet, an ambassador for Henry III to the Netherlands and a friend of her brother Hercules, was also at this gathering, and he planned to escort Philippe on her journey. Mondoucet strongly encouraged Margot to join the voyage to Spa, and Philippe de Montespedon quickly echoed his sentiments.

Mondoucet had an ulterior motive for his suggestion; he’d recently returned from Flanders, where he was pursuing the potential Dutch alliance on Anjou’s behalf. When he suggested she join their party, Margot “understood his intentions, that no doubt it was in service of the Flanders campaign.”4

Princess Philippe, it seems, had no inkling of these political underpinnings. This is probably why when Philippe approached Catherine de Medici, asking permission to bring Margot along in her travels, the Queen Mother actually said yes.

The Journey

The plan was rather straightforward. The travelers would require a series of wealthy hosts who could provide room and board as they made their weeks-long journey towards Spa. Margot’s role was to locate potential allies in the provinces, to gauge interest in Anjou’s cause and smooth his entry into Dutch politics.5 Ahead of the journey Margot spent several days with her brother, as he “instructed her in the offices he desired of her for his campaign in Flanders.”6 They would have discussed who she would meet, their politics, their lineages and existing alliances. Armed with this information, Margot gathered the traveling party at her chateau in La Fère, where they departed in May 1577.

The group traveled through Picardy where they met Louis de Berlaymont, the Catholic Archbishop of Cambrai. Margot characterized Berlaymont as having a “Spanish heart” - meaning she should keep her campaign secret in his company. Berlaymont escorted the travelers to Cambrèsis, where they met the first ally who Margot had been encouraged to win over: the Lord of Inchy, governor of Cambrai.7 Her task proved easy, as he soon requested leave to join Margot’s traveling party, confessed to her his hatred for the Archbishop, and encouraged Anjou to intervene. Marguerite de Valois must have made a strong impression on the governor: she won his loyalty quickly, he remained a partisan of her cause throughout her campaign.

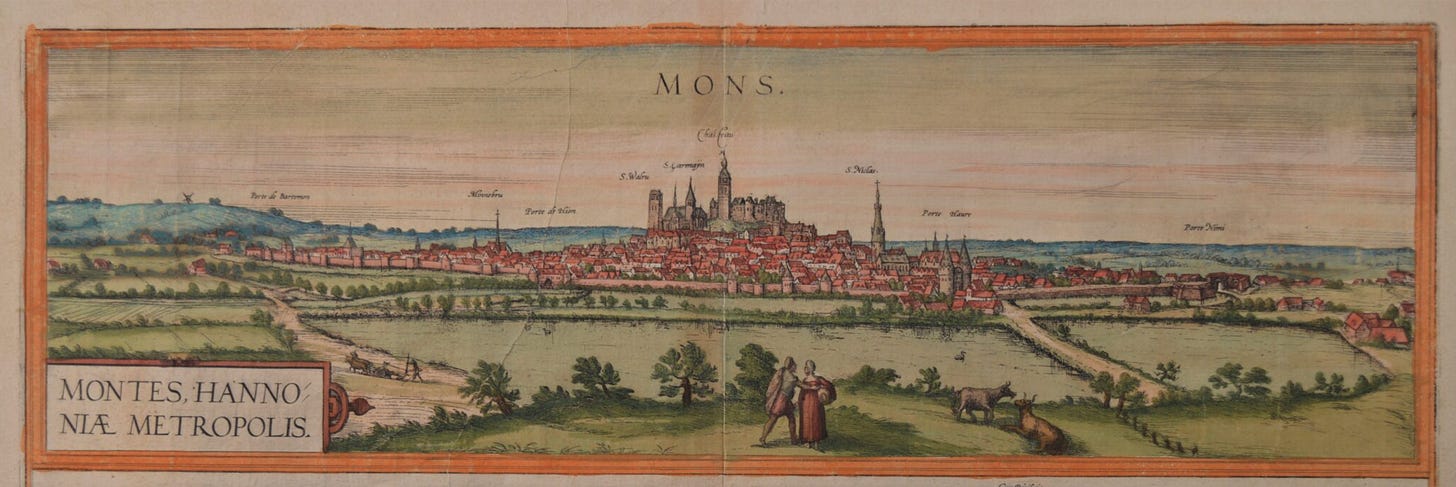

Mons

The group continued through Valenciennes and on to Mons, the capitol city of the Province of Hainault. Margot’s stay in Mons proved one of her most important successes. The party was hosted by the Count and Countess of Lalaing, southern Catholics who nevertheless seemed open to the idea of a replacement for Philip II. The Count of Lalaing was both governor of Hainault and a member of the Dutch States General. The count was well positioned to advocate for the Anjou if Margot could win him over.

In Margot’s own telling, it was the Countess of Lalaing who proved the more eager and valuable ally. The Countess was Margaret de Ligne-Arenberg, a daughter of Margaret de la Marck-Arenberg and her husband, Jean de Ligne. I covered Margaret de la Marck’s rise to power in my most recent post, so it suffices to say that the Arenberg were a powerful Catholic dynasty who split their time and attentions between the two halves of the Habsburg empire.

But more on Margaret de la Marck later. Margaret de Ligne’s political goals were quite distinct from her mother’s. Though this was not always the case, it seems that the Countess aligned herself more directly with the interests of her married family than the policies of her parents. The Lalaing’s political rise began in earnest with the onset of the Dutch revolt, so the countess brought the prestige of the older Arenberg name into her marriage.8 She also held significant influence with her husband, and it seems the pair enjoyed a true political partnership.9

Margot wrote at length about her stay with the Lalaings at their court, which she described as dominated by “eighty to one hundred ladies.”10 The travelers were fêted with an impressive ball, including dinner, music, and dancing, but towards the end of the evening, a private conversation between the countess and Margot turned towards politics.The countess decried the recent abuses of the Spanish government towards the Netherlandish nobility - in particular, the executions of the Counts of Egmont and Horn, “who were our close relatives,” was the final straw, as it was for many in the Netherlands.11

Margot could not promise French support, per se: the campaign needed to make significant progress before they would risk bringing it to Henry and Catherine’s attention. She instead offered the eager and generous support of her younger brother Anjou, and made the case for his leadership. The Countess of Lalaing promised that she would raise the issue with her husband, and the two women spent the rest of the evening discussing “anything that might serve the design.”12

The informal, even intimate nature of the conversation was a hallmark of women’s diplomacy in this age: pursuing political negotiations within social parameters, their machinations subtle under the guise of noble courtesy. And yet, the countess’ comment was a direct call foreign aid to oust the Spanish.13 The following day, Margot and the countess were joined by the Count of Lalaing, and together they discussed next steps for their alliance. Margot arranged for the Lalaings to meet with Anjou, at her château in La Fère, later that year. The party remained in Mons for a full week, due to the hospitality of the countess, and when they finally departed Margot promised to visit again during her return journey.

Namur

Upon leaving Mons Margot had to flex her skills in deception rather than persuasion. They arrived in Namur, capital of Wallonia, where the Archbishop of Cambrai had arranged their reception by Spanish Governor Don Juan. With the governor were two noblemen, Charles-Philippe de Croÿ, Marquis d’Havré and his brother Philippe III of Croÿ, Duke of Aarschot. The Croÿ brothers came from an ancient and powerful Netherlandish family, and politically they advocated a middle ground: they’d been central to the signing of the recent Edict of Pacification between the States General and Spain.14 Peace was maintained for the moment, but Governor Don Juan increasingly saw the Croÿ brothers as a threat to his own position.15

Diane de Dommartin, Baroness of Fénétrange and Countess of Fontenoy, was a formidable matriarch, sovereign in Lorraine, with lands in France and the Empire. She was also the wife of Havré (their marriage more of a promotion to his standing than her own).16 Only two years prior, Diane’s niece Louise de Vaudémont became Queen of France when she married Margot’s brother Henry III.

Don Juan had requested that Diane travel to Mons to join Margot’s reception there, and she escorted the group as they made their way from Mons to Namur. Don Juan would have depended upon Diane to report on any questionable activity among the party. Margot’s mémoires don’t mention Diane until after the group left Mons, so it seems Diane kept to the sidelines as Margot became close with the Countess of Lalaing.17 This makes sense, as well, since the Croÿs remained loyal to the Spanish government: Margot and the Lalaings would have kept their negotiations quiet in her company. Diane also escorted the party from Namur to the town of Huy, returning to Namur once they were received by the Bishop of Liège.18

Liège

The party finally arrived in Liège at the end of July, eight weeks after leaving France. They resided in Liège, rather than Spa, as it offered more comfortable amenities for an extended stay - but Spa was close enough for them to access the waters daily. Liège was also a more convenient location for receiving the many “ladies from Germany,” as Margot described them, who came to visit her.

So now we return to the letter from Margaret de la Marck that exposed me to this whole story in the first place. In a strange turn of events, it was the Duke of Aarschot, Philippe III of Croÿ, who had requested that Margaret de la Marck and her son Charles visit Queen Margot in Liège. The Croÿ and d’Arenberg were families closely linked through marriage, as well as politics.

Circumstances for the brothers changed dramatically after Margot departed Namur. Governor Don Juan seized the citadel, nullifying the concessions he’d agreed to in the Perpetual Edict, forcing Aarschot and Havré to flee to Antwerp to request the protection of the Dutch States General.19 Aarschot’s request for the Princess of Arenberg to visit Queen Margot makes more sense in this context: Aarschot and Havré were both adapting in real time, writing to any friends who might have connections to potential allies.

Unfortunately for Aarschot, Margaret de la Marck wanted nothing to do with all this. She didn’t want to get involved in Don Juan’s coup, Aarschot’s scrambling, or really the Dutch revolt at all.

Margaret de la Marck’s immediate interests lay more in the Empire than in Spain. Within the last year Margaret and her son had been promoted to Princess and Prince of the Empire in recognition of their service to the Emperor. Marguerite de Valois described The Princess of Arenberg as “a lady held in high esteem by the Empress, the Emperor, and all Christian princes.” Other than that, Margot didn’t write much about Margaret de la Marck. Margaret de la Marck had no interest in Marguerite de Valois, either, but her correspondence shows how her visit to Liège fit into her family management.

Margaret de la Marck’s letter was addressed to her close friend Joanna of Hallewyn - wife of Philippe III of Croÿ, Duke of Aarschot. Margaret explained that she was preparing for the upcoming marriage of her daughter Antonia Wilhelmina, so Aarschot’s request was an inconvenient distraction. Wedding planning required her attention, but Margaret de la Marck’s travel motivations, like Margot’s, were two-fold. Her priority was to protect her son Charles from being called up into Don Juan’s war, and with tensions again on the rise, she planned to take her family to Germany as soon as possible.

It stands out that Margaret was writing to Joanna of all people to complain about Aarschot’s request. Because she did so, we can assume that Joanna sympathized with the desire to protect her family and the two women understood each other - and after all, Margaret did make the trip to meet Margot, although she didn’t put it to any political use. In fact, Margot’s mémoires imply that she didn’t learn news of Don Juan’s coup until much later - meaning Margaret de la Marck declined to inform her.

Clearly Joanna Hallewyn and her husband weren’t Margaret’s main concern: that was Don Juan. Her son Charles would need express permission to leave the Netherlands: as a leading young nobleman, he could be called up to military service. But Margaret was determined that Don Juan would grant her son leave. To be more assured of his acquiescence, Margaret traveled to Namur herself to face down the governor.

This was a shrewd decision for Margaret de la Marck, because she knew Don Juan could not risk losing her support. His violent uprising had stirred outrage, creating an even more powerful excuse for Netherlandish nobles to turn against Spain. The knowledge that Margaret de la Marck would be traveling to the Empire - with her son or not - was a powerful crossroads for the governor to consider. Her friends and contacts there would certainly ask her about recent developments in the Netherlands. Margaret might respond in a way that explained Don Juan’s actions - or she might add to the growing murmurs that Spain’s hold in the Netherlands was crumbling.

How do we know that Don Juan had this concern in mind? Because of how he responded to Margaret’s request. As Margaret told Joanna, Don Juan regaled her with a full account - his account - of how his coup had occurred:

he told me that [my request] was reasonable, then shared his account of his recent troubles and of the retreat to the chateau, assuring me he did not want war but to continue the peace, and that he would go to the States General, from whom he awaited response - though I do not know how this gesture was received. He said he did not want to let the states fall into greater ruin and desolation by a new war, and promised that it would not happen. Upon which I left with my son, and was happy to be doing so.

By granting Charles’ leave, Don Juan could only hope that the Princess would echo his narrative when she reached the Empire. In any case, Margaret was relieved to await the fallout from the relative safety of Arenberg:

I assure you this news and these missions give me such pain and regret, to see affairs reduced to such terms, that often I do not know what ends I should pursue, considering what may follow and the evil that might arise if things are not remedied ... However I decided that, God willing, I will leave with my sister and my three children from here in five or six days to go to Arenberg and give order to all that I can.20

Margaret’s instincts served her well. Don Juan did not, in fact, maintain peace in the Netherlands, as Marguerite de Valois and her traveling party soon realized for themselves.

The Return

After six weeks in Liège, Margot’s party departed in September 1577. Soon thereafter she had a chance meeting with Diane de Dommartin, where she finally learned of the governor’s coup. Don Juan had sent Diane to escort the travelers from Namur, and he orchestrated his takeover during her absence. When she returned, her husband and brother-in-law were gone. After an imprisonment of several weeks Diane managed to escape Namur. She was now, similar to Margaret de la Marck, making her way out of the Netherlands.

In-the-weeds historical research sidebar:

Some contemporary pro-Spanish sources alleged that Diane actually sided with Don Juan, and even that she became his lover during this time. Given the complete lack of evidence for that, and what we’ve learned of the situation, What Margot tells us of Diane’s account seems more realistic. Were Diane free to depart Namur of her own will, she had no reason to remain - her husband and his brother were now in open rebellion, and Don Juan had proved himself unpredictable and rash. Diane’s safest option was to depart for Lorraine to await developments from a position of sovereignty and personal security.

Back to Margot. She heard Diane’s story with alarm and saw the effects of the coup for herself, as the locals they met grew increasingly hostile and suspicious. With Diane’s warning, Margot’s party hastened their journey west.

Delays for the travelers mounted. The passport they required to cross the Netherlands never arrived, and when the party decided to risk traveling without documentation, local officials pressured members of Margot’s retinue to stall, seemingly at the behest of Don Juan. Her treasurer claimed they had no funds to continue their voyage, and the town seized the party’s horses. At this point the elderly Princess of La Roche-Sur-Yon stepped in: “The Princess de la Roche-Sur-Yon would not support this affront, and seeing the danger I was in, provided the necessary funds, and we left while they were still in confusion.”21

But it wasn’t only Don Juan who sought to detain Margot. Once back on the road, Margot received a message from her brother Anjou:

[Henry III] greatly repented allowing my voyage to Flanders, and he tasked his people on my return to cause me some bad turn, through the Spanish who he’d alerted to my work in Flanders for [Anjou].

Anjou himself was also part of this problem. The soldiers he’d been amassing were underpaid and began pillaging, ransacking the very towns in the Franco-Dutch borderlands whose support he required. Not only did Margot need to look out for the French King’s men, but local communities were liable to show her hostility as well.

The town of Dinant soon made good on this threat. When the local leaders recognized who Margot was they detained her party, hoping to cash in on a promised reward from Don Juan. That is, until Margot said the right name at the right time. The town of Dinant was under the purview of the Count and Countess of Lalaing, and her mention of the couple caused an immediate reversal in the people’s conduct:

The oldest among them asked me, smiling and stammering, if I was truly a friend of the Count of Lalaing; and myself, seeing that his kinship served me more than those of all other lords in Christendom, responded: yes, I am his friend, and his kin as well.” From then they revered me, the man offering me his hand and as much courtesy as they’d previously given insolence, begging that I excuse them.22

Margot and her party were free to continue their travels. What’s more, someone sent word of the confrontation to Mons, and Countess Margaret of Ligne promptly sent an armed guard to escort the party for the remainder of their journey.

The Aftermath

Once comfortably installed in her château in La Fère, Margot vowed that she would risk no more travel until a peace was signed. But her diplomatic work did not end. Margot and Anjou hosted a series of interviews with the Lalaing in La Fère - the meetings she had first discussed with the countess in Mons. The Count of Lalaing roundly endorsed Anjou’s pitch and praised Margot for her support. When Anjou came to an agreement with Orange and the States General, the governing body wrote their own letters of thanks to Margot, recognizing her role in their alliance with her brother Anjou.23 Even Henry III and Catherine de Medici had to reckon with the alliance developing between Anjou and the Dutch: Margot attended a reception with the King, Queen, and Queen Mother in St. Denis, where she thrilled the courtiers with stories from her travels. The campaign had reached a point that convinced Henry and Catherine to finally entertain its potential.

Margot from this point enjoyed a stronger standing with her brother and mother. They no longer impeded Margot from traveling to Navarre, and they employed her diplomatic prowess when the French crown undertook its next series of peace talks with the king her husband.

Anjou, unlike his sister, was unable to capitalize fully on the boon her diplomacy had provided. Anjou and his forces joined together with the Prince of Orange in Mons in the latter half of 1578, but due to chronic financial problems, poor management of troops, and his growing realization that his kingship was nothing but an honorary title, Anjou returned to France only a year after Margot’s campaign.24

Throughout the Anjou campaign and to its bitter end, the Lalaings remained Anjou’s most avid supporters. The Croÿ brothers worked with the French Prince but kept their options open, while Margaret de la Marck kept her family in Arenberg until the death of Don Juan and the installation of her own friend Margaret of Parma to replace him. Diane de Dommartin’s husband Havré became an ambassador for the Dutch States General to England, but Diane opted to remain in Lorraine for the next several years - she insisted that if her husband wanted to see her, he should make the journey to her court to do so.

Some closing thoughts

Marguerite de Valois’ legacy has long been dominated by questions of sexual deviance and brazen conduct, but her campaign in the Netherlands shows another side of her completely. She took initiative to support her younger brother and put herself at significant risk in the process, but her work paid off, kickstarting the most politically successful period of her life.

This story included so many different people (and definitely too many Margarets). But I wanted to highlight each of the women Margot met in her travels to show that she was not a powerful woman working in isolation. It was quite common, even expected, for women to take active roles in diplomacy and politics. Not only did singular, “exceptional” women gain access to political power, but there were countless women at every level of society who worked to protect themselves, their families, and their interests in response to a changing political landscape. The choices made by the Margaret de Ligne, Diane de Dommartin, and Margaret de la Marck highlight their distinct motivations and political strategies, and how they leveraged meetings with the Queen of Navarre to pursue their own interests.

If you’d like, you can also:

Mack Holt, The French Wars of Religion: 1562-1629, 2nd ed. (Cambridge University Press, 2005), 105-106; and The Duke of Anjou and the Politique Struggle During the Wars of Religion (Cambridge University Press, 1986), 28-50.

Arlette Jouanna, La France du XVIe Siècle: 1483-1598, 502.

Caroline zum Kolk, éd., État de la maison de Catherine de Médicis, 1547–1585 (BNF Ms Fr nouv. acq. 9175, f. 379-394).

Éliane Viennot, Marguerite de Valois: Histoire d’une femme, histoire d’un mythe (Paris: Payot, 1993), 101.

Rita Mazzei, “Il viaggio alle terme nel Cinquecento. Un ‘pellegrinaggio’ d’élite fra sanità, politica e diplomazia,’” Archivio Storico Italiano 172, no. 4 (2014); 649.

Marguerite de Valois, Mémoires, in Collection Complète des Mémoires relatifs à l’histoire de France, Claude Bernard Petit, ed., ser 1. t 37. (Paris, 1823), 103. I recognize that Marguerite de Valois composed her mémoires decades after the events under discussion, so we must read them with a grain of salt. Anything facts I cite from her mémoires I’ve cross-checked with other reputable sources, and where speculation is required I have done my best to explain why reasoning.

De Valois, Mémoires, 106.

Violet Soen, “La Nobleza y la Frontera Entre Los Países Bajos y Francia: Las Casas Nobiliarias Croÿ, Lalaing y Berlaymont en la Segunda Mitad del Siglo XVI,” in Fronteras: Procesos y práticas de integración y conflictos entre Europa y América (siglos XVI-XX), Favarò, Merluzzi y Sabatini, eds., (Fondo de Cultura Económica, 2017), 431.

Peter Neu, Margaretha von der Marck (1527-1599): Landesmutter, Geschäftsfrau und Händlerin, Katholikin. Eine Gefürstete Gräfin in Einer Zeit Grosser Umbrüche, (Enghien: Fondation d’Arenberg, 2013), 8.

De Valois, Mémoires, 109.

Viennot, Marguerite de Valois, 97.

De Valois, Mémoires, 211; Israel, The Dutch Republic: Its Rise, Greatness, and Fall, 1477-1806 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1995), 156-60.

De Valois, Mémoires, 113.

Violet Soen, “Négocier la paix au-delà des frontières pendant les guerres de religion: Le parcours pan-européen de Charles-Philippe de Croÿ, marquis d’Havré (1549-1613),” in Noblesses Transrégionales: Les Croÿ et les frontières pendant les guerres de religion (Brepols: 2021), 357-365.

Anton Van Der Lem, Revolt in the Netherlands: The Eighty Years’ War 1568-1648 (Chicago University Press, 2019), 113-114.

Nette Claeys & Violet Soen, “Les Croÿ-Havré entre Lorraine et Pays-Bas: Les engagements politiques et religieux de Diane de Dommartin, baronnesse de Fénétrange et comtesse de Fontenoy (1552-1617),” in Noblesses Tranrégionales, 338-340.

Soen, “Négocier la paix”, 248.

De Valois, Mémoires, 119.

Van der Lem, Revolt in the Netherlands, 120; Soen, “Négocier la paix,” 341-343; Mirella Marini, “Female Authority in the Pietas Nobilita: Habsburg Allegiance during the Dutch Revolt,”" Dutch Crossing 34, no. 1 (March 2010); 6-7.

Margaret de la Marck to Jeanne Hallewyn, September 1577, Fondation d’Arenberg (Enghien) ACA MM 46.

Marguerite de Valois, Mémoires, 129

Marguerite de Valois, Mémoires, 132.

Documents concernant les relations entre Le Duc d’Anjou et Les Pays-Bas (1576-1583) Muller & Diegerick, pubs. (Utrecht, 1889) t. 1, no. 50. GoogleBooks.

Holt, Duke of Anjou, 105-110.