Mary, The Final Sovereign Duchess of Burgundy

The Ruling Ladies of the Low Countries, Part One

Welcome to fifteenth-century Burgundy!

As I said in the introduction to this series, the story of female rule in the Netherlands begins in the Duchy of Burgundy, which was an independent, sovereign region ruled by a line of Dukes descending from the French Valois dynasty. In the late 1300s, the youngest son of French king Jean II had married Margaret III of Flanders, the widow of the last Duke of Burgundy, uniting the multiple Burgundies under one ruler.

Loosely defined, there were three Burgundies – the provinces to the northeast of the French Kingdom, which included Artois, Flanders, Holland, Luxembourg, and Brabant, comprised the Burgundian Netherlands. The Duchy and County of Burgundy were situated along the eastern border of France near modern-day Switzerland. As you might notice from the map below, the Burgundies were conspicuously interrupted by the presence of Lorraine.

The Duchy of Burgundy under Charles the Bold

Burgundy expanded through the amalgamation of independent provinces, French fiefs, and German lands over the course of the fifteenth century.1 Through these acquisitions and a series of deft marital alliances, Burgundy became one of the most powerful duchies in western Europe. Relations between Burgundy’s dukes and their ruling French relatives remained fraught, but Burgundy worked in alliance with England to counter the power of France.

The court of Burgundy was an epicenter of medieval art, music, and courtly culture, arguably peaking under Charles the Bold, who came to power in 1466. Charles was the great-grandson of the first Valois Duke of Burgundy, and the father of its final sovereign Duchess, Mary.

Charles the Bold’s plans for his Duchy were, well, bold. Specifically, he wanted to expand Burgundy to achieve the borders of the ninth-century kingdom of Lotharingia. Lotharingia had been the middle kingdom separating east and west Francia: these three kingdoms were divided among three grandsons of Charlemagne. At that time, Lotharingia had stretched from the Mediterranean to the North Sea.2 At the heart of this old kingdom was Lorraine, which had since become an independent duchy.

Naturally, none of Burgundy’s neighbors were keen on Charles’ plan. These Duchies and fiefdoms defended themselves from Burgundian aggression through alliance with France. The French king Louis XI became Charles the Bold’s greatest rival, and proved the single greatest threat to Mary of Burgundy’s sovereignty after Charles’ death.

Charles had married the sister of Louis XI, Catherine, when the two were children, but Catherine died when Charles was only thirteen.3 Charles remarried eight years later, at the much more appropriate age of twenty-one, and he found true love and companionship with his second wife, Isabelle of Bourbon. Mary was born three years later, in 1457.

Charles and his father, Philip the Good, both certainly hoped that Mary was the first of many children – eldest sister to a few brothers would be the best-case-scenario. When Mary was baptised two weeks after her birth, Duke Philip did not even attend. His relationship to his son Charles tended to be fraught (a dynamic he had in common with Louis XI and his own father, Charles VII). Apparently Duke Philip felt that, as his first grandchild was only a girl, the ceremony was not worth the trip.4

Mary enjoyed a comfortable if lonely childhood. She was raised at the Chateau of Quesnoy until she was six years old, but proximity to the French border grew problematic alongside her father’s escalating feud with France. From then on, Mary spent much of her time in Ghent. She did not have much of a relationship with her mother or grandmother in her youth, but was educated by women selected by her parents, learning the ropes of courtly culture and ducal politics from a safe distance.

Mary spent much of her free time in these years in the company of animals: Quesnoy housed a grand menagerie, and she was fond of the monkeys and most of all the parakeets, gifts from her mother, sent all the way from Africa.5 Her love of animals was a constant throughout her life, and as she grew older ambassadors knew that gifting her parakeets could earn her goodwill.

Mary was eight years old when she was finally to reunite with her mother, who she had not seen since she was two years old. Mary was with her father in Ghent, and Isabelle journeyed to join them by way of Antwerp. But Isabelle died before she arrived, most likely of syphilis. From then on Mary resided at the Coudenberg Palace in Brussels, closer to the action of the court, closer to her father, but mostly in the keeping of her grandmother, Isabel of Portugal.

Honor and History: A Source in Mary’s Household

Mary’s position in the succession - especially now that her mother had died - meant that an elaboration of her household was in order. It was natural for ladies-in-waiting to transfer between households: they provided continuity and smoothed the arrival of a young heiress to the court, educating her in the mores and intrigues of her new surroundings.

One of these ladies, Éléonore de Poitiers, had been a staple at the Burgundian court since she was seven years old. She first joined the household of Isabelle of Bourbon as a demoiselle d’honneur in 1458.6 Éléonore came into Mary of Burgundy’s household when Isabelle died in September 1465, and she remained there until 1482.7 After a brief retreat from public life - Éléonore falls out of the record around Mary’s death - she returned to the fore as a dame d’honneur in the household of Jeanne of Castille, the wife of Mary’s son Philip the Handsome, in 1496. By the end of her life she had been in the inner circle of three consecutive Duchesses of Burgundy.

Luckily for us, “This lady Alinor wanted to put into writing all that she saw, and all she heard said by her mother, during the time that they resided at the Court of Burgundy.”8

She wrote her manuscript, which eventually became known as Les Honneurs de la Cour, between 1484 and 1487.9 In it she shared her experiences and explained the role of honor in the organization and politics of courtly life. She wrote about issues of precedence between courtiers, how service was structured, and provided rich details regarding the material luxuries of the court.

For our purposes, Éléonore’s commentary on the birth and baptism of Mary of Burgundy explains the complicated relationship between Louis XI and Charles the Bold. Louis XI became the greatest threat to Burgundy, but he was also Mary of Burgundy’s godfather.

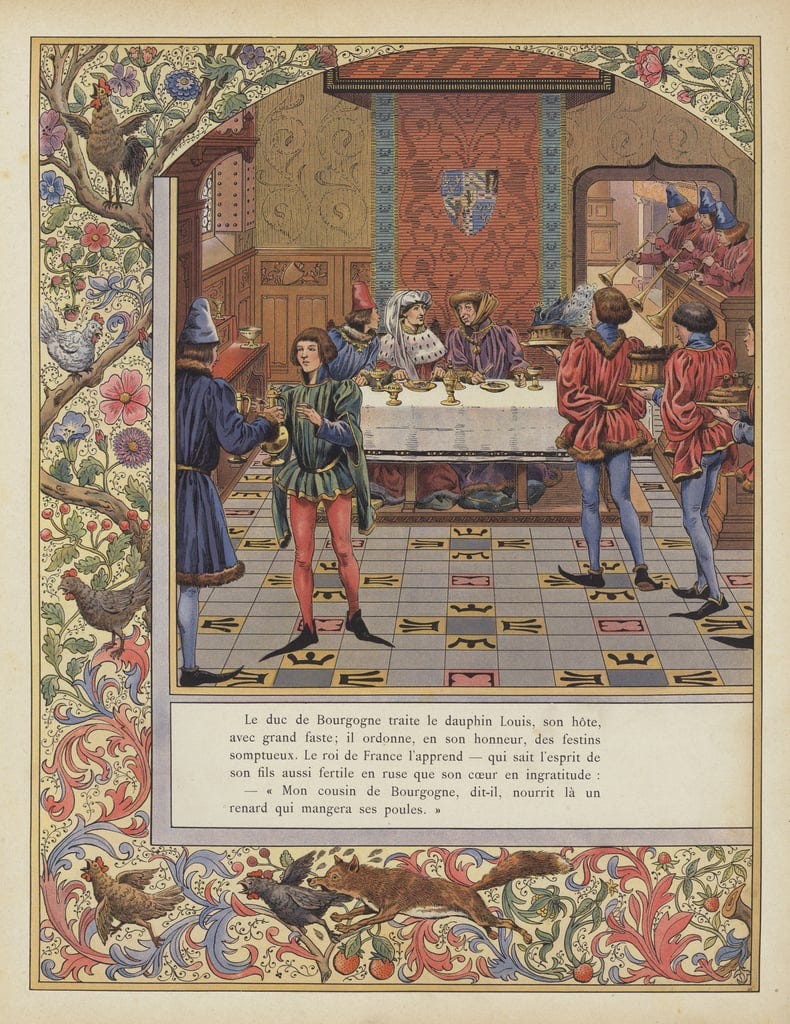

Éléonore witnessed herself when the then-Dauphin Louis arrived in Brussels, on the heels of some disagreement with his father the King, “as he had no other place to live.”10 Duke Philip was in Utrecht fighting a war at the time, so his wife Isabel of Portugal and daughter-in-law Isabelle of Bourbon had been the ones to receive the dauphin, to hear his plea for asylum and make him welcome. When Mary of Burgundy was born, the dauphin was still in residence.

Isabel of Portugal carried Mary to the baptismal font, and Louis accompanied her in the ritual. Éléonore wrote “I’ve heard it said by those who would know that Monsieur the Dauphin presented the child because no one else could be found who was his equal, to join him at Madame’s side, as it was such a great honor.”11 Louis was not chosen for this role through affection, but because of his rank; he happened to be in the right place at the right time. The culture of honor that proved so central to Éléonore’s descriptions of court created the circumstances for what would in a few short years appear an epic betrayal.

The Arrival of Margaret of York

Charles the Bold had been so devastated by Isabelle’s death that, even when he announced his desire to marry for a third time, Mary’s position in the succession did not appear vulnerable. Charles had no desire to replace his late wife, but he sought the political and economic benefits of a new alliance. Margaret of York, the sister of English King Edward IV, presented an opportunity to bolster their alliance against Louis XI.12

Given Charles’ lack of interest in his new bride, Margaret of York was able to focus completely on Mary. At the time of the marriage Charles was 35, Margaret of York 21, and Mary of Burgundy 11 years old. Margaret quickly became both a sister and a mother figure to Mary, and she would remain her loyal advocate for her entire life.

Charles and Margaret developed a productive and mutually respectful relationship. Charles tasked Margaret on multiple occasions to strengthen his alliance with her brother Edward, at least once sending her with an embassy to England. But Margaret’s strongest legacy was her fierce protection of Mary of Burgundy.13

Around the same time another woman came into Mary’s inner circle. Madame de Hallewyn became central to Mary’s continued education and a trusted confidant for both Mary and Margaret in their most challenging moments. Philippe de Commynes - a contemporary witness and primary source on the courts of Louis XI and Charles the Bold, whose mémoires provide much of the detail we have for these years - claims her as his cousin: he identifies her as Jeanne de Clite, dame de Commynes, the widow of Jean seigneur of Hallewyn.14

Her surname Hallewyn intrigues me, because another powerful noblewoman, Jeanne de Hallewyn, has already made an appearance here - she was a close friend of Margaret de la Marck, Duchess of Aarschot, and the mother of Anne de Croÿ! I’m hoping I can figure out more specifically how these two women, separated by a century, were related.

Margaret of York and Charles the Bold married in 1468, and Mary enjoyed the next nine years in the loving company of her stepmother, slowly preparing for her inheritance of Burgundy. But the inheritance arrived much sooner than either of them had hoped. In pursuit of Lotharingia, Charles the Bold’s forces went up against an alliance of French, Swiss, and Austrian forces near Nancy on January 7, 1477. It’s unclear exactly how this went so poorly, but Charles the Bold was killed, eleven years into his reign.

The immediate aftermath of the battle brought much confusion and doubt. It was both difficult and crucial to definitively identify that it was, in fact, the Duke Charles whose body had been recovered. While agents for Burgundy sought confirmation, King Louis XI’ messengers moved more quickly, informing their king of the death of his great rival within three days of the battle. It would be weeks longer before Mary or Margaret were informed of Charles’ demise. As it turned out, only their trusted friend Madame de Hallewyn could convince them that the rumor was true, to spur them to action to respond to his loss.15

The Reign of Mary of Burgundy

We can imagine why Mary, at nineteen years old, would hold out hope that her father had somehow survived. Mary was inheriting a Duchy in crisis, with men seeking to take advantage of her youth and vulnerability on all sides.

Louis XI had quickly marched his men towards Dijon, arguing that the French tradition of female exclusion from the throne - Salic Law - meant Mary had no valid claim to rule, and therefore Burgundy should revert to French rule.16

An in-the-weeds historical research sidebar…

Salic Law was a cited in France as a law forbidding women from inheriting the French throne, or the throne passing through female lines of inheritance. In reality, the Salic Law was cited from a document conveniently “recovered” out of the archives at St. Denis when the first Valois King, Philip, usurped the rights of his niece (and coerced wife), Queen Jeanne, on the death of her parents and infant brother. The document was actually an old legal code about property inheritance, not rulership (and even property rights for French women varied widely by region). But it was in Latin, and this was the fourteenth century, so Philip could claim it said whatever he needed it to. To this day many histories still reference Salic Law as if it were a straightforward French law. But it wasn’t! And even people with power at the time knew that it was something of a scam, due to the number of French men who tried to marry daughters of kings in an effort to gain power themselves.

Louis XI had long angled for a marriage between Mary and his own son and heir, the Dauphin Charles. When Charles the Bold died Louis decided to pivot, to claim as much of Burgundy as he could by force, while Mary and Margaret rushed to establish her government.

The Burgundian provinces and the deputies who represented them were divided over what to do. Mary, now twenty years old and only weeks into her unexpected acquisition of power, decided to present herself and call for her people to stand against France. In Ghent, she moved up a planned meeting of the Estates to defend her claim.17 In letters to her governors, officers, and men of accounts, Mary affirmed her rights through her knowledge of history, reminding them that Jean the Good had gifted Burgundy to his son - not as an apanage of France, but to be ruled independently.

Her well-researched arguments were not heard by all of the estates deputies – in Dijon, for instance, the deputies declined to read her letter aloud at their meeting. The region had quickly sided with France, as it was the first that Louis invaded, and he’d promised to honor their traditional privileges and establish a permanent parliament for their governance. These gestures, alongside his violent suppression of those who resisted, made for a powerful argument.

The people of Flanders, still smarting from limits Charles the Bold had placed on their own rights and privileges, decided to throw their lot in with France, as well.18 The County of Burgundy, which abutted the Duchy headed by Dijon to the east, declared for Mary under the leadership of the Prince of Orange.

As the provinces fractured around her, Mary hoped to revive any goodwill that might remain from Louis’ residence in her grandfather’s court.19 She and Margaret of York sent an embassy to Louis with a personal letter, hoping some sort of accord was still possible. But Louis XI played their outreach to his advantage, claiming that the letter was proof that Mary had tried to make deals without the input of her own officers. The rumor spread and further inflamed revolts in the provinces, stoking chaos to divide Mary’s attentions and resources.

The Marriage Question

Mary and her most adamant supporters agreed that she needed the support of a marital alliance. As the richest heiress in Europe, she had plenty of suitors for her hand. Both the French King and the Holy Roman Emperor had sons who made good candidates. King Edward IV and Margaret of York discussed an English match, with Margaret recommending their brother George, the Duke of Clarence, and Edward angling for his brother-in-law, Anthony Woodville. But this was a short lived discussion, literally: Edward and George had an existing feud that escalated over the disagreement, and George seemingly drank himself to death soon after.20

The question became one of the Empire versus France, and the Estates were naturally split over who Mary should choose.21 Margaret of York favored Maximilian Habsburg, and she informed the German ambassadors how to gain Mary’s interest and goodwill.22

Maximilian was a more practical choice than Charles, the son of Louis XI. While the French Dauphin was seven years old, Maximilian was eighteen. An older husband meant that Burgundy could expect heirs much sooner, which was an important consideration given the fragility of her position. Commynes reported that Madame de Hallewyn expressed this argument most vividly:

“Madame de Hallewyn … said they needed a man, not a child, as Mary was woman enough to bear a child and the country needed one. No one blamed the lady for having spoken so frankly, others avowed, saying that [Mary of Burgundy] spoke of nothing but marriage, because it was such a necessity for her country.”23

Here Commynes added a personal note which reminds the reader of his French biases: after stating the logic of the French alliance, he concluded “But God wanted a different marriage, and on my word I still do not know why.”

It seems rather clear why Mary would go against the French option. For all of Louis XI’ shenanigans, attacking her cities, spreading rumors, and turning her people against her, it’s no wonder that Mary preferred Maxmilian, the question of age aside. Simon Winder might have explained it best: in winning Mary’s hand, the Holy Roman Emperor gained for his son and heir “what Louis XI might have had in return for a little civility.”24

It’s worth noting how quickly all of this went down: her father died in January, and Mary and Maximilian’s marriage procuration occurred on April 21 of the same year. Mary had considered and turned away a slew of suitors over the course of three hectic months.

Happily Ever After, for just a little while

The all-important first meeting between spouses was carefully choreographed: Maximilian was first received by Mary’s trusted protector, Margaret of York. He had Margaret to thank for the success of his suit, and he embraced her in thanks. Only then did Margaret bring Maximilian to meet Mary, in the company of her ladies-in-waiting.

Madame de Hallewyn was crucial to these early days, as neither bride nor groom spoke the other’s language. Mary had no German, and Maximilian no French. Madame de Hallewyn was their translator, and she helped Maximilian gain Mary’s affection, providing valuable insights into the behaviors and gestures that would be received most favorably by his new wife.25

All the chroniclers attest that the marriage turned into a love match. Mary and Maximilian actually shared a bedroom - highly uncommon in the period - and they often spent evenings listening to music and playing games. They liked to spend winters in Bruges, where they enjoyed ice skating together, and they gradually taught each other their own languages. They threw parties, and Maximilian in particular enjoyed singing to and entertaining their guests.26

Mary invited intellectuals and artists from across Europe to her court. She hosted debates on the ancient philosophers and patronned the visual and material arts that had defined the court of her youth. In this way Mary and Maximilian continued to promote the glorious reputation of the Burgundian court, despite the deprivations brought by Louis XI’s aggression.

Mary and Maximilian were personally happy and productive.27 Mary gave birth to a son, the future Philip the Handsome, at Bruges in 1478. (Louis XI was committed to his meddling, and he spread a rumor that the child born was a girl. I guess hoping to disappoint a people who were, quite literally, already ruled by a woman?) Two years later she had her daughter, Margaret, at the Coudenberg Palace in Brussels - named for Margaret of York, of course, who was also godmother to both children.28

Mary and Maximilian were a united front in the fight for Burgundy, but Mary remained the sovereign: her son was her heir, Maximilian her consort. Mary employed Margaret of York and Maximilian as her deputies. Margaret handled international diplomacy, securing protections for Burgundian trade with England. Maximilian took charge of the war effort, to reclaim the lands lost to France in the early months of 1477.

But relationships strained in the course of time. Maximilian began to fear that Margaret of York was too partial to England, while Mary found Maximilian lacked sufficient weight to manage the French threat alone. Mary increasingly came to the fore of her own government, particularly from 1480, after Margaret of Austria’s birth. Mary undertook a series of journeys across her provinces to see to their administration and secure the coalition of her supporters in person.29 She understood that she had to be the one to lead, and be seen leading, Burgundy.

Mary took pains to encourage the loyalty of her nobles and to return families to favor who had fallen out with her father. She made promises recognizing the concerns and privileges of each of her provinces, and she promoted noble leaders in the crucial borderlands with France, encouraging their loyalty with lands, army positions, and other forms of patronage.30 Her policy of respecting each province’s unique characteristics would remain a crucial element of any future governance that hoped to rule in the Netherlands.

The Death of Mary of Burgundy

Now we come to the part I’ve been dreading. Writing about elite pre-modern women, it’s a lovely and rare thing to learn about women gaining true happiness in their married life. At the same time that Mary was building a loving relationship with the husband she chose, she was also developing her political instincts, cultivating her allies and charting her own path as ruler - all in her early twenties. But the potential she represented for Burgundy’s future was tragically cut short.

In March of 1482, Mary took part in a hawk hunt near Bruges. She rode side saddle, as was her preference, and for some unknown reason, her horse reared. This might not have been so devastating had the girths of her saddle not loosened, her saddle spun. Mary fell backwards off her mount, landing on her hands and knees. The mare fell backwards on top of her.

Mary was crushed under its weight, her hands completely deformed as she’d tried to catch her fall. Her wrists were snapped backwards and broken.31 A modern exhumation of her body found that she had broken four ribs on her right side, and when she died - a brutal five days later - it was due to a hemo-pneumathorax.32

Mary was rushed to the Prinsenhof in Bruges to the care of her doctor, though she apparently declined a thorough examination in the interest of modesty. She likely knew that her wounds would be fatal, and sought to preserve her dignity where she could. But she made the most of her painful final days; she dictated her will, stating that Maximilian would be in charge of the children’s education - their tutelle - while Margaret of York would oversee their gouvernance - their moral upbringing, personal care, and happiness. She named Maximilian Regent on behalf of their son Philip, now Duke at four years old, and she tasked him to continue the fight against France.33

Margaret of York had been in Malines, near Brussels, when she learned of Mary’s accident. She rushed to Bruges and did not leave Mary’s side until the end. After completing her testament, Mary said her goodbyes to Maximilian, Margaret, and Madame de Hallewyn. I’ve not found evidence of whether she saw her children. She died on March 27, 1482, at twenty-five years old. She had only ruled for five years.

Mary of Burgundy was beloved by her subjects, and her loss was a devastating blow. Even the pro-French Philippe de Commynes wrote “her death was a great shame for the people, for she was a great woman and liberal, and well-loved by her subjects, and she showed them greater consideration and reverence than did her husband: she was also a lady of that country… a lady of great renown.”34

Mary of Burgundy’s short rule represented the end of an independent Burgundy, but the rule of her female descendants would keep her legacy alive to the Netherlandish people. The Netherlands might have become Habsburg -and eventually Spanish - in name, but they remained Burgundian in essence.

Mary remains a popular figure in the region to this day, as evidenced by this delightful beer that I stumbled upon (strangely not in Belgium, but at a craft beer shop in Washington, D.C.!)

Commynes was right when he wrote that Maximilian Habsburg did not enjoy the adoration of the Netherlandish people. Commynes had called Maximilian a “young German oaf,” and spoke broadly of the rude behaviors of the German people as a whole, but in this specific case his biases don’t make him wrong - Maximilian did struggle to retain his position after Mary’s death. The Estates rejected her testament giving Maximilian the tutelle of the children and his prerogative to continue the war.35 Even those who hated France now found Burgundy’s position too vulnerable to forego a negotiation.

The deputies of Ghent seized custody of the children and they agreed to a marriage between the two-year-old Margaret of Austria and Charles of France - the same boy who Louis XI had hoped would marry Margaret’s mother.36 The toddler was sent under cover of night and without a chance for farewells, for fear that Maximilian and Margaret of York would try to intercept her. Margaret spent her childhood under the watchful eye of Charles’ elder sister, and eventual governor, Anne of France.

If they had butted heads in the past, the loss of Mary of Burgundy brought Maximilian and Margaret of York together again. Margaret remained one of his revered political advisors, and though she received many proposals of marriage since Charles the Bold’s death, she never considered any option but to remain in Burgundy. Especially once Maximilian was elected Holy Roman Emperor, Margaret oversaw the care of the young Duke, Philip the Handsome. She raised Philip to be a good prince and gentleman, and she led marriage negotiations for both children for years to come - for as we’ll see, Margaret of Austria’s life in France was only the beginning of her story.

The age of the Burgundian Dukes ended with Mary of Burgundy, and the era of the Habsburg Netherlands began. But for the Netherlandish people, hope remained that they might one day return to the glory of the Duchy of Burgundy. They had good reason to hope, because Margaret of Austria – Mary’s daughter – would grow up to ensure the faithful governance of her lands and the political future of Mary’s most famous descendant: her grandson, Holy Roman Emperor Charles V.

If you’ve enjoyed this post and would like to contribute financially to my writing, you can also:

Thank you so much for your support!

Katheryn A. Edwards, Families and Frontiers: Re-Creating Communities and Boundaries in the Early Modern Burgundies (Leiden: Brill, 2002), 8-9.

Mack Holt, “Burgundians into Frenchmen: Catholic Identity in Sixteenth-Century Burgundy,” in Changing Identities in Early Modern France, 346-350.

The marriage was a stipulation of the 1435 Treaty of Arras: Philip the Good had agreed to acknowledge Charles VII, rather than Henry VI, as the King of France, while Charles VII agreed to punish the French men who had murdered Philip the Good’s father, Jean the Fearless, during the Armagnac-Burgundian feud of the Hundred Years’ War.

Louise-Marie Libert, Dames de Pouvoir: Régentes et gouvernantes des anciens Pays-Bas (Paris: Éditions Racine, 2005), 21.

Libert, 35.

Jacques Paviot, “Éléonore de Poitiers, Les États de France (Les Honneurs de la Cour): Nouvelle édition par Jaques Paviot,” Annuaire-Bulletin de la Société de l’histoire, 76.

Aubrée David-Chapy, Anne de France, Louise de Savoie, inventions d’un pouvoir au féminin (Paris: Classiques Garnier, 2016), 618.

Éléonore de Poitiers, Honneurs de la Cour, BNF Ms Fr 14353 fol. 1-2. Gallica.

Paviot, 77.

Poitiers, fol. 27v

Poitiers, fol. 43v.

Libert, 23.

Simon Winder, Lotharingia: A Personal History of Europe's Lost Country (Farrar, Straux and Giroux, 2019), 143.

Philippe de Commynes, Mémoires, in Collection Complète des Mémoires relatifs à l’histoire de France ser. 1, t. 12 (Petitot), 332-333. Gallica.

Winder, 145.

Edwards, 9.

Jean-Pierre Soissons, Marguerite: Princesse de Bourgogne (Paris: Bernard Grasset, 2002), 17.

James B. Collins, The French Monarchical Commonwealth, 1356-1560 (Cambridge, 2022), 203.

Soissons, 18.

Winder, 145.

Soissons, 22

Commynes, 335.

Commynes, 333.

Winder, 147.

Libert, 55.

Libert, 25.

Lisa Hopkins, Women Who Would Be Kings: Female Rulers of the Sixteenth Century (Vision Press, 1991), 144. Internet Archive.

Mary had a third child, a son, who died in infancy.

Libert, 58.

Violet Soen, “The House of Croÿ and Mary of Burgundy. Or, How to Keep Noble Elites at the Burgundian-Habsburg Court (1477-1482),” in Marie de Bourgogne/Mary of Burgundy: ‘Persona’, Reign, and Legacy of a Late Medieval Duchess / Figure, Principat et Postérité d’une Duchesse Tardo-Médiévale, Michael Depreter, Jonathan Dumont, Elizabeth l’Estrange, and Samuel Mareel, eds. (Brepols, 2021.)

Soissons, 26.

This condition occurs when blood and air fill up the lung cavity, compressing the lungs until they are unable to expand and take in air. My thanks to my mom (MD), who provided this grisly yet clarifying explanation.

Hopkins, 145.

Commynes, 340.

Soissons, 26.

Hopkins, 145.